At the end of October 2025, a small group of activists from Dresden — members of Anarchist Black Cross, malobeo, FAU and Queer Pride — set out on a solidarity trip to Ukraine. We packed a van full of materials collected in Dresden and hit the road, not just to deliver supplies, but to connect with people and collectives who, in their own ways, are resisting the Russian full-scale invasion. Our goal was also to learn and to listen to those living through the war, to exchange stories and experiences, and to weave stronger networks of solidarity.

The journey starts with a long drive toward the Ukrainian border — which somehow feels shorter than the five hours we spend waiting to cross it. Late that night, we finally reach Lviv, where Shelter from the Lviv Vegan Kitchen opens his doors to us.

Shelter is a vegan activist, food relief enthusiast and volunteer army combatant. Right after the beginning of the full-scale invasion, he joined a territorial defense unit, but after a couple of months, he returned to Lviv to become a vital part of Lviv Vegan Kitchen collective. At the same time, Shelter is now serving on rotation basis in a voluntary artillery unit. One reason to join a voluntary unit was also to have bigger freedom of choice where to go and what to do.

In wartime, people find their own ways to help — their own spaces where they can feel they’re contributing something. For the crew behind Lviv Vegan Kitchen, that space is food. The collective formed in the early days of the full-scale invasion in 2022, when thousands of refugees were fleeing west. They decided to cook for them, funding everything entirely through donations.

Until June 2024, the kitchen served up to 500 hot meals a day to internally displaced people. When donations ran dry, that part of their work had to stop — but the collective didn’t. They realized there was another gap to fill: food for vegans on the frontline. Military rations provided by government are not vegan and in case there is a kitchen in the unit, meat or cheese are being mixed in the dishes so there is no vegan option.

So the kitchen started to cook, bake and send packages to the front – falafel, seitan, syrniki (Ukrainian curd pancakes), cookies, and other durable vegan meals that can survive long journeys and rough conditions. They even came up with their own protein bar recipe, which, according to soldiers, is a huge hit.

We visit their storage space. It’s DIY, improvised, and full of heart: shelves stacked with carefully labeled bags and boxes, a chest full of vacuum-packed seitan and falafel. Everything run with surprising order and precision. Here, Shelter prepares the packages with vegan ready-made food but also fills zip bags with basic spices, makes sets of instant soups and tomato paste, weighs out yeast flakes and soy granules; so soldiers have everything to prepare themselves a decent vegan meal. To receive a package from Lviv Vegan Kitchen, they only need to fill out an online form — and somewhere along the supply line, one of Shelter’s packages will find its way to them.

Learn more about Lviv Vegan Kitchen: www.lvivvegankitchen.com

You can support them with donations here: telegra.ph/How-to-donate–YAk-zadonatiti-06-13

On the long drive to Kyiv, we download mobile apps that send alerts about air raids. You can choose which regions you want notifications for. We also join a handful of Telegram channels, some run by volunteers, others by official institutions, that post updates whenever missiles or drones are detected. Not long into the drive, our phones start buzzing and wailing one after another. Air raid alert for Kyiv. Air raid alert for Sumy region. The app politely advises us to “find the nearest shelter and stay calm.” We’re not even close to those regions yet, but the nonstop alarms become too much. We switch our phones to silent and pretend not to notice. The alarm stops with a person from the phone announcing: “May the force be with you.”

By the time we roll into Kyiv, the city of nearly three million feels strangely calm. Public transport stops at 10 p.m., metro stations close soon after, and by midnight the curfew empties the streets.

The next day, we meet two members of the Student Union Priama Diia, which translates as Direct Action. One has long curly hair tied back in a ponytail and wears a sweater that reads NO PHOTO. The other, with a shaved head and dangling earrings, smiles as they wave us over at the metro station. Across the street, we see a factory, which is bombed on a regular basis, without glass in the windows.

As we walk together through the neighborhood, we pass another burnt-out building. But around it, life moves on — people heading to work, carrying groceries, chatting at market stalls. In spite of the ongoing war, Kyiv is very much alive.

We arrive at a self-organized space inside the art university. The room feels both improvised and full of care — we sit down on DIY sofas made from wooden pallets, covered with a colorful crocheted blanket, next to a small bookshelf stacked with zines and books. Abstract geometric paintings hang on the walls, and smaller pieces are displayed on minimalist shelves. It feels like a living room gallery or a social center.

The student union Priama Diia has been around since the early nineties, passing through several generations of activists, ceasing to exist just to be reborn after some years. The two members tell us how, in 2023 — a few months after the start of the full-scale invasion — they began rebuilding the union from just three people. They saw how urgently students needed a voice, especially in the time of war. Now there are around 300 members across different cities in Ukraine.

Their work ranges from fighting scholarship cuts and dormitory evictions to confronting psychological abuse and power imbalances from teachers. They push to make education fair and accessible — “for the benefit of students, not the deep pockets of the one percent,” as they put it. They organize events, protests, and publish zines about how students live and find strength for activism during the war.

On the table in front of us, the two members spread out the union’s stickers and flyers. A black cat appears again and again — in one version inside a circle, echoing the antifascist logo; in another, it’s wearing a pink bowtie and reads “Solidarity” in Cyrillic. Hello Kitty with an AK-47. Marx Bubu in a bunny onesie. Nestor Makhno.

For the union, education isn’t a privilege or a commodity. It should be free and accessible for all. It should be anti-capitalist. They see the student struggle as part of the wider labor movement — not just a fight for better study conditions, but part of the broader struggle for human liberation.

You can learn more about Direct Action Student Union here: www.priama-diia.org

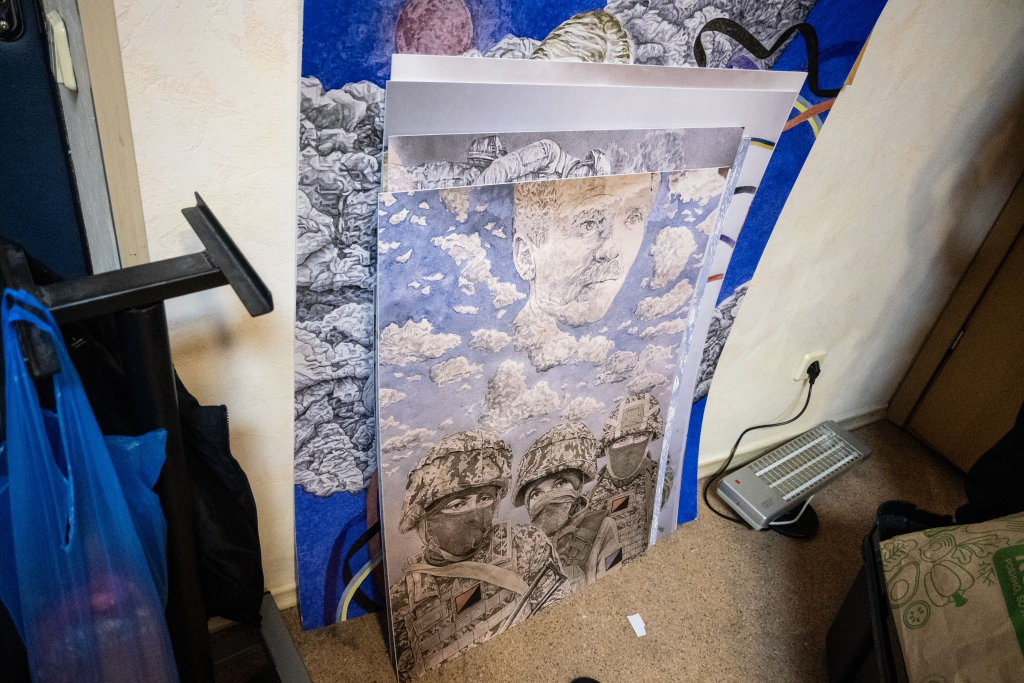

In the afternoon, we meet several activists in the office of Solidarity Collectives. Above us hang anarcho-feminist and antifascist flags; on a shelf a painted portrait of the Russian anarchist Dmitry Petrov who died in 2023 in Bachmut fighting Russian imperialism; on the floor, a few paintings by the Ukrainian anarchist artist David Chichkan, who was killed this year at the frontline. One shows three soldiers with anarcho-feminist and anarcho-syndicalist flags on their uniforms — small emblems on their chests and sleeves. Behind them stretch white clouds across a blue sky, and within the clouds, a faint portrait of Nestor Makhno, as if the sky is mirroring an inspiration of the current struggles.

We meet Iryna from Feminist Lodge. That’s a grassroots initiative founded in Kyiv in 2017 that promotes gender equality. Since the beginning of the war, they’ve shifted their focus to helping vulnerable women and their families with humanitarian aid, distributing it across the countryside—including temporarily occupied territories — and to internally displaced people.

You can learn more about Feminist Lodge here: www.instagram.com/feministlodge

We meet Andriy from Sotsіalniy Rukh (Social Movement), a Ukrainian left-wing organization that supports workers across industries — from mining and transport to healthcare, education, and IT. In 2022, they called on the international left to support Ukrainian resistance to Russian imperialism and spoke out against the government’s wartime rollbacks of labor rights.

You can learn more about them here: https://rev.org.ua/sotsialnyi-rukh-who-we-are/

Then we meet Mykola from Solidarity Collectives — yellow curls, small silver earrings across the earlobe, a retro jogging jacket that would fit right into Berlin, and black cargo pants. He looks tired, smoking hand-rolled tobacco.

The collective consists of anti-authoritarians who came together when Russia’s full-scale invasion began. They support anti-authoritarian comrades fighting on the frontline and those affected by the war — providing humanitarian aid, building FPV drones, and support animal rescue.

Mykola tells us about the endless rotation of volunteers, a too small group of active people, how everyone is tired. At the start of the invasion, he worked in humanitarian aid, driving to bombed-out villages in the east to bring materials and help displaced people rebuild their homes. One day, he returned to find those same houses reduced to rubble again, their inhabitants once more forced to flee. The futility of Sisyphus work hit him hard. Now, he builds drones for anti-authoritarian soldiers at the front.

You can learn more about Solidarity Collectives here: www.solidaritycollectives.org/en

What connects all the collectives we meet today is a deep exhaustion. After nearly four years of war, burnout has become one of their biggest challenges. There’s always another crisis, another person who needs help. No time to rest after their work and activism. Yet through all the fatigue, they remain kind and patient — their smiles sometimes delayed, but genuine when they arrive.

Suddenly, a power outage. These happen often now and are increasing due to the Russian attacks on Ukraine’s energy infrastructure. Sometimes they’re planned, sometimes not. Local energy suppliers or the municipality provide tables of planned outages on their websites or Telegram channels, so people can get prepared.

For the night following our meeting at Solidarity Collective’s office, a massive air attack is expected. Telegram channels fill with warnings. Locals seem unfazed: “Air alerts happen every day,” they say, “you can’t live in a shelter forever.”

Around 1 a.m., one of the comrades wakes us. We quietly gather our things, step into the cold, and head to a nearby garage serving as a makeshift shelter. We spread our mats behind parked SUVs, slip into our sleeping bags, and listen to the sirens and the distant rumbling of air defense. Or is it someone snoring, and we’re making it up? A family with small dogs passes by, carrying their own camping things. We spend the night there.

By morning, we learn it was one of the biggest aerial attacks since the start of the war — over 700 projectiles, among them drones, cruise missiles, and decoys raining across the country. We open a picture of visualized attacks through this night, and the whole map of Ukraine flares: Strike UAVs “Geran-2/Harpyia,” cruise, ballistic, and air-launched ballistic missiles — “Kh-101, Iskander-K, Kalibr,” “Iskander-M,” and “Kinzhal”, decoy drones identified as “Gerbera.”

Some of us look up the military terms online, still unsure what they are and what they mean. The official statements say Russia is targeting energy infrastructure and “military objects,” but factories, homes, and civilians are hit just the same.

Later, we visit Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) which is a deeply historical, emotional place for Ukraine: A wave of demonstrations and civil unrest, the “Hundred Dead of the 2014 Revolution”. Today, rusty barricades from the uprisings ornament the side of the road, together with informational signs, describing the riots, a flash photo of a crate with Molotov cocktails.

The square features a large red monument that reads I ♥ Ukraine, reminiscent of the I ♥ Paris or I ♥ London signs. Around it stretch thousands upon thousands of yellow and blue flags, each bearing the name of someone killed in the full-scale invasion. Here and there, clusters of other flags appear — those of the U.S., Georgia, Belarus, and in one small corner, a few anarchist flags. We see a portrait of a young person known by the nickname “Anarchia”.

Workers, or perhaps simply locals who care for the place, gently pick fallen leaves from the yellow-and-blue plastic flowers and sweep the ground. People move quietly along the narrow paths of the memorial. A man with a prosthetic hand stands motionless on the steps, crying. He limps through the sea of flags marking the dead. The gendered violence of this war — mostly directed at male bodies — hits painfully.

From Maidan, we take the metro to Babyn Yar, where we meet our other comrades.

The park is quiet and vast, the trees shedding their yellow and orange leaves onto the ground. Monuments are scattered around. It’s a terrifying place. 33,771 Jews (according to the murderers) were slaughtered in two days during World War II, more than in any other single massacre committed by the Germans. All in all, between 1941 and 1943, the Nazis murdered approximately 100,000 people, including almost the entire Jewish population of Kyiv, in the ravines, which were located here before, during Soviet Union, the whole area was remodeled. Babyn Yar is a dark landmark on the map of the Holocaust — the site of the largest mass shooting carried out by the Nazis during their campaign against the Soviet Union.

We pass a rusted iron structure shaped like an old Romani wagon, wrapped in a chain of iron flowers, some candles on the stones underneath it. It’s a monument to the Roma killed in Babyn Yar. Behind it stands an old tractor, ready to maintain the lawns and trees next to it.

We walk deeper into the park. Joggers pass us, people walk their small dogs, life quietly continuing around a place of unimaginable horror. We reach a contemporary audiovisual installation called Mirror Field, about the size of a small basketball court. It’s made of stainless steel — a circular mirrored platform with ten tall columns rising from it. The surfaces are shot through with bullets of the same caliber the Nazis used here during the executions.

The description of the installation says that at its center is the symbol of the Tree of Life, found in so many religions and myths. The tragedy of Babyn Yar shows how easily this tree can be destroyed, its branches broken. From the columns, organ-like sounds emerge — music made from the names of victims, turned into tones. We walk slowly across the mirrored surface, looking at our shot-through reflections, listening to echoes of Yiddish songs from the 1920s and 1930s. We can’t escape our own reflections.

You can read more about Babyn Yar here: https://babynyar.org

In the evening, we take the metro to Podil, a vibrant neighborhood in Kyiv. Someone needs a bathroom, and a comrade tells us you can ask anywhere in Ukraine for water or a toilet — no one will refuse or demand payment.

We climb a hill where local activists planted a tree in memory of Dima Petrov, an anarchist killed in this war. It’s already dark, and we stumble through the night until we find the tree. From the top, Kyiv unfolds before us — huge and glowing. You can see the left bank too, and the bright spinning lights of the Ferris wheel. Then, an air alert siren cuts through the air. Phones buzz with notifications. Someone checks the attack map, but a comrade from Kyiv reassures us: “They don’t target places like this. Don’t worry.”

We head downhill. Podil feels a bit like Dresden’s Neustadt — backyard raves, student bars, late-night shops, gay clubs, beautiful facades. The people look great, confident; even here, some wear puppy masks. A few streets further, it feels like an industrial zone.

We wanted to see how young people live here. Someone asks Iryna from Feminist Lodge what the clubs in Kyiv are like. She smiles, writes down a few names, and says: “They’re good, but the best raves are in Kharkiv. People there party differently. They’re so close to death that they’re more alive.”

Then suddenly, another power outage. The neighborhood goes dark. Convenience stores and bars turn on their generators. It’s loud, dark, and smells of gasoline — but life goes on.

On the following day, some of us head off to visit Chernobyl museum, a history museum in Kyiv, dedicated to the 1986 Chernobyl disaster and its consequences. The museum is under construction and closed. Sacks of cement and construction materials lie around. Above them hangs a display of road signs from villages abandoned after the disaster — each one crossed out, marking the end of a place. In the souvenir shop, bullet casings from this war are painted with radiation symbols. A Chernobyl safety suit stands beside them like the body inside evaporated, and a toolbox with radiation detectors lies on the floor. A kind staff member offers us augmented reality goggles that take us through the history and the massive structures of the Chernobyl Power Plant.

Chernobyl is not just history — it feels present again. With Russia’s invasion, cuts of external power supply at the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, and the reports of Russian soldiers digging trenches near Chernobyl at the start of the war, stirring up radioactive soil, the danger feels very real. This feeling just increases as, during our stay, we hear the news that the Russian army started to hit substations of nuclear power plants in Rivne and Khmelnytskyi, several hundred kilometers west of Kyiv.

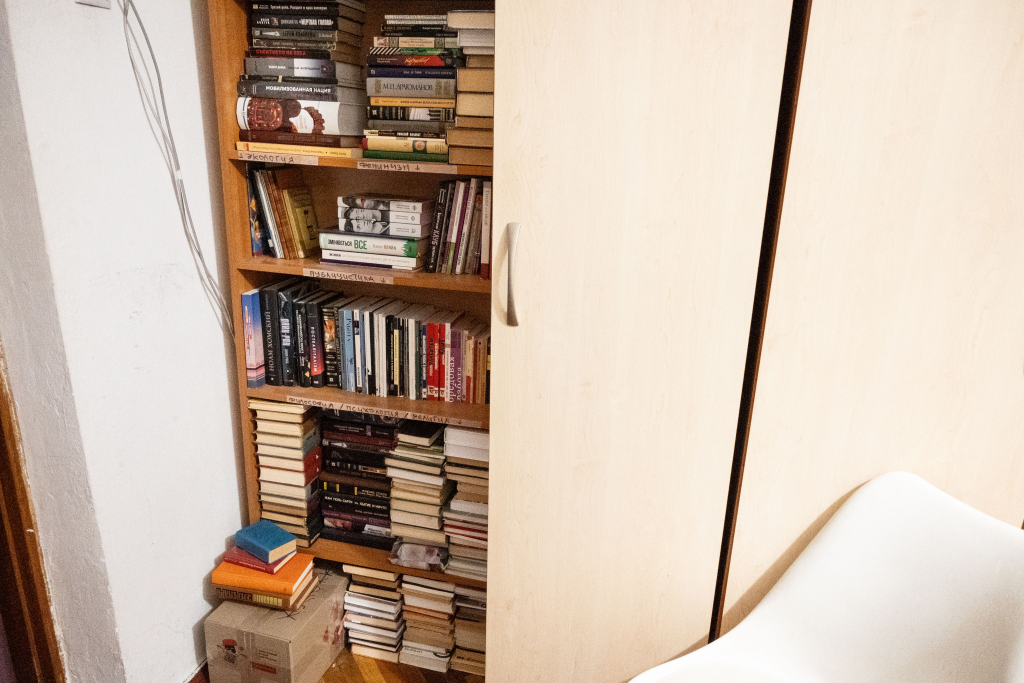

That evening, our group meets Kateryna who runs an anarchist library that currently exists only online. We meet at her former flat where the books are stored right now. She can’t live here anymore as the neighborhood keeps getting attacked from the air. “It’s too stressful,” she remarks.

Kateryna greets us in her small kitchen with tea, waffles, and jelly fruit. She has long curly hair and speaks Ukrainian, but switches to Russian to make it easier for us to understand. She shows us how they digitalized the collection. She is happy that even soldiers on the front borrow books from the library. “It gives me hope,” she says, “when they write that the books help them pass the time and feel less alone.”

She shows us her former bedroom: a mattress on the floor, pushed as far from the window as possible. The window is not existing anymore, the frame is taped over with plastic and duct tape; the glass is completely eradicated due to the shelling. On the sill, there’s a collage of stickers: Anti-Fascist Action, Nestor Makhno, Death to Imperialism, Animal Liberation – Human Liberation, Respect My Existence Or Expect My Resistance, Cats Against Putinism. Across from the mattress, a bookshelf holds anarchist and feminist books; Emma Goldman’s face looks out from her memoirs, translated into Russian just a few years ago. Kateryna digs out some local feminist zines.

The anarchist library in Kyiv is existing since 2013, in 2017, Kateryna started to take care of it, it got the name Vilna Dumka (“Free Thought”) and found a place in an anarchist bar. It also held bar nights, workshops, and other public events, but had to close down due to the high rent. As the public place is not available anymore, people can lend books online. On her phone, Kateryna scrolls through their online catalogue — around 300 titles, from classical anarchist theory to activist memoirs, feminist texts, and writings on ecology, animal liberation, migration, and labor struggles.

The goal of the library is to make theory and practice of anarchism available to anyone who wants to learn more about the ideas of freedom, equality, and the struggle for human rights, especially today, when people in Ukraine are fighting for their freedom and independence.

The library is looking forward to book donations in Ukrainian and English on topics of anarchism, social and environmental issues, feminism.

You can find out more about Vilna Dumka here: https://vdbooks.org/

On the way to our accommodation, we pass people wearing eccentric make-up. Some women wear cat ears, others wear goth white and black drawings on their faces. Someone in a white wedding dress with a white veil over their face, strides by a line of tanks on the roadside in Kyiv. It’s Halloween.

The next morning at 6 a.m., we leave Kyiv in a convoy to head to the humanitarian trip we planned to support. It is organized by Oksana from Solidarity Collectives. She is responsible for the humanitarian work of the organization. She is nearly permanently on the road, establishing contacts to grassroot initiatives in the regions near the frontline or evacuating animals from abandoned villages and towns. The perfectly renovated motorway stops after some hours of driving, roads get bumpier, smaller. We drive through villages and towns with high apartment blocks, pass Dnipro to come to Pavlohrad, a town of about 100,000 inhabitants, shaped by its omnipresent mining sector. The trip takes about nine hours.

We arrive at a small house with an outdoor toilet and a few people standing around the yard — displaced families, some fleeing war for the second time, many of them coming from Dobropillia or other mining towns in Donetsk region. Olha, the woman who is organizing humanitarian aid here in town, opens her yard and garage for organizing support.

We unload the cars — duvets, pillows, mini ovens, microwaves, kettles, pet food, toys, power banks, kitchen utensils, electric heaters — things we gathered in Dresden or bought in Kyiv. People from the area come to help, and soon a human chain forms; everyone is willing to take part. Afterward, people line up to collect what they need while Olha and others organize the distribution. She kneels on the ground, dividing dog and cat food from large sacks into the small bags people have brought with them.

Olha is volunteering already since 2014, firstly supporting soldiers on the front line. After the beginning of the full-scale invasion, her work shifted towards the support of refugees. In Dobropillia, she had an office and worked together with different initiatives, among them Solidarity Collectives. But as the Russian army started to heavily hit the town with guided bombs in August 2025, she had to flee herself. She took refuge in Pavlohrad where her husband got offered a job at the local mine. They rented and renovated a small house on their own cost, as she emphasizes, even though their only source of income is the husband’s salary. Meanwhile, she tries to adapt to the changed conditions and continue her voluntary work.

It’s getting dark. In the garden, they’ve set a table with biscuits, fruits, tea, and coffee. We stand around chatting. Some speak Russian, others Ukrainian. A few words in English. Nodding. Many people here are organized with the Independent Miner’s union of Ukraine. The tell us about how the work in the mines has changed due to the war, how they continue to fight for higher wages and better working conditions but also how they collect donations for union members fighting right now on the front line. One man, a local miner, helps displaced people to find work at the local mines. Another shows us a still from the film 20 Days in Mariupol, pointing at the building which is just hit by artillery: “That was my balcony,” he says quietly. He lost everything and doubts that he will get any kind of compensation, even if the war ends. He wears a headlamp, and we can see only the light and our shadows on the ground as we stand in the backyard, sipping tea.

Another man’s phone plays the sound of running water — it’s his notification tone for air alerts. He starts calling somebody, obviously getting nervous. In the distance, we hear Shahed drones. Someone says they sound like motorcycles from afar. Then comes a deep, booming bass from the air defense system. The drone is shot down.

We drive to Poltava, where we booked hotel rooms for the night, but halfway there, the Solidarity Collective’s car hits a deep pothole and destroys two tires. We spend hours searching for someone to carry the car to a garage which could get it fixed till next morning, and after dozens of phone calls and asking around we are successful. Shortly before the curfew starts, we arrive at our hotel.

In the morning, we continue to Sumy, a city of about 250,000, only thirty kilometers from the front line. We pass through areas which were occupied during the first months of the war. Road signs are sprayed over — to confuse the Russians, someone says. Billboards hang torn or replaced with army recruitment posters and food advertisement.

At a gas station several kilometers before Sumy, our Ukrainian friends remind us to keep two tourniquets each in case of bleeding. “If you see a Shahed drone, park under a tree,” one says. “And if you see us running — run too.” With a weird feeling in our bellies, we pass by destroyed bridges, new-build trenches and checkpoints to finally reach Sumy.

We’re met by Anja, who helps us find a parking spot and leads us through a small alley. A woman in a stylish jacket passes by with two little dogs dressed warmly. We end up in a café, full of spider and spiderweb decorations and scary jack-o-lantern pumpkins. The time slows down. It’s her café, she took it over from people who decided to leave the city. She invites us in for a free coffee. Thirty kilometers from the front line, she offers plant-based milk and cream, and she serves us a Halloween-themed drink called Spooky. In this café, they offer free coffee for soldiers. Visitors can donate the cost of a drink and leave a post-it note with a message to lift the soldiers’ spirits.

Anja pulls out her phone and shows us photos of herself and other women from Sumy at shooting practice. They receive training in tactical medical aid and how to use a gun from a former army officer. During the day, she also works as a doctor. She keeps herself busy and helps her community in every way she can.

We deliver the donations to a former student’s dormitory now housing elderly refugees from the east. In the common room, pink and white balloons scatter around the floor like a birthday party has just taken place there. People move slowly, some with walkers. Some invite us into their rooms to tell their stories. Most of the people come from small villages near the Russian border which got completely destroyed and already live in the dormitory for over a year.

We talk to an elderly couple, Volodymyr and Tamara, whose daughter was killed in a shelling attack. Tamara did heavy work all her live, working in a mine and loading and unloading freight trains, in order to provide a home for her children. But all of that is gone now. They say that they are already old and probably won’t live long enough to see the end of the war, and they only hope to not die under shelling or while hiding from bombing in a basement.

Svetlana tells us about how she made it out of Mariupol. After the beginning of the invasion, she had to spend one month in the city, in a hell on earth, as she puts it. There was permanent bombing and shelling, apart from one hour a day, maybe the lunchtime of the Russian soldiers. She saw how quarters were bombed, to which Russian soldiers previously directed them for evacuation. In her flat, the doors and kitchen were destroyed by shelling. She and her mother-in-law survived by hiding near the elevator shaft. As she moved through the city to find a way out, she saw corpses lying behind partition walls which read to the front russkiy mir – the Russian world. “Yes,” she says, “that’s the Russian world, only blood, death, and corpses.” After making it to Berdyansk, an occupied city west of Mariupol, she finally got evacuated by the Red Cross. On the way the bus passed 34 checkpoints and one each of them all men were searched and got their telephones checked. Svetlana tells us how, during the time in Mariupol, her brain switched on some kind of protective mechanism. How she used to stare for days at the wall not moving. How she started crying for days just after being rescued and fell into a deep depression, unsure if she wants to continue to live or not.

In these stories, the horror of the war hits us hard, we find it hard to leave our new acquaintances behind, but we have to leave before it gets evening and another night of aerial attacks begins. While the sun settles in a red and dramatic sunset, we drive back to Kyiv.

The next evening, we hold a small discussion in an antifascist gym — sitting in a circle on the training mats, boxing bags hanging behind us, a green Antifascist Action flag with the Rojava symbol above, a queer flag to the side. We talk with local activists about solidarity work, about how Ukrainian refugees are treated in Germany, about their legal status, and about the problem of “toxic antimilitarism” among some Western leftists, who refuse to support those resisting Russian imperialism. Someone mentions the Berlin book fair that excluded Eastern European comrades who do solidarity work — a small example of a bigger issue.

This gym where we’re sitting is self-organized. They offer boxing and calisthenics training, and host political events when they can. Many of their trainers are now fighting at the front. They rely on donations to pay rent and keep the space alive.

Please donate if you can: https://send.monobank.ua/jar/6a2pKZJxvs

On our last day, we visit a huge exhibition at Kyiv’s main train station called Ukraine WOW. It’s not an activist project but a cultural one — telling the story of Ukraine through geography, history, and art. It’s a way of reclaiming identity and countering Russian propaganda.

One part that stays with us is the work of Maria Prymachenko, a self-taught folk artist from near Chornobyl. She attended school for four years, before contracting polio, leaving her with a physical impairment, which impacted her life and art. Her paintings and embroideries are full of color and strange, joyful creatures — lions or maybe bulls with tiger stripes on pink grass, images from fairy-tales and folk traditions.

Then we drive back through Poland to Germany. Somewhere on the highway, the internet signal disappears — like slipping into a dark hole.

These were long and short days at once, full of contradictions. Moments when people say, “Everything’s fine,” even as exhaustion shows on their faces, and moments when you sip a Halloween Coffee Latte while worrying about drones to suddenly appear over your head. Times when you feel intensively the proximity of war, and times when you almost forget about it. Listening to the stories of displaced people, hearing about their murdered relatives and friends, and seeing the material consequences this war has caused, it’s hard to not feel enraged at how moralizing and judgmental some Western leftists can be. Our full solidarity goes to everyone living through this war and to the ones who continue to resist.

(A)

Don’t forget, we’re still finishing the donation campaign. Please, donate: https://www.betterplace.org/en/projects/162495

We changed the names of people to protect them.